Tests of Big Bang: The CMB

The Big Bang theory predicts that the early universe was a very hot place and that as it expands, the gas within it cools. Thus the universe should be filled with radiation that is literally the remnant heat left over from the Big Bang, called the “cosmic microwave background", or CMB.

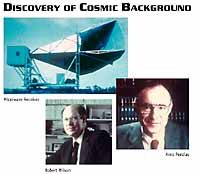

Discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background

The existence of the CMB radiation was first predicted by Ralph Alpherin 1948 in connection with his research on Big Bang Nucleosynthesis undertaken together with Robert Herman and George Gamow. It was first observed inadvertently in 1965 by

Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson at the Bell Telephone Laboratories in Murray Hill, New

Jersey. The radiation was acting as a source of excess noise in a radio receiver they were

building. Coincidentally, researchers at nearby Princeton University, led by Robert Dicke

and including Dave Wilkinson of the WMAP science team, were devising an experiment to find

the CMB. When they heard about the Bell Labs result they immediately realized that the CMB

had been found. The result was a pair of papers in the Astrophysical Journal (vol. 142 of 1965): one by Penzias and

Wilson detailing the observations, and one by Dicke, Peebles, Roll, and Wilkinson giving

the cosmological interpretation. Penzias and Wilson shared the 1978 Nobel prize in physics

for their discovery.

The existence of the CMB radiation was first predicted by Ralph Alpherin 1948 in connection with his research on Big Bang Nucleosynthesis undertaken together with Robert Herman and George Gamow. It was first observed inadvertently in 1965 by

Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson at the Bell Telephone Laboratories in Murray Hill, New

Jersey. The radiation was acting as a source of excess noise in a radio receiver they were

building. Coincidentally, researchers at nearby Princeton University, led by Robert Dicke

and including Dave Wilkinson of the WMAP science team, were devising an experiment to find

the CMB. When they heard about the Bell Labs result they immediately realized that the CMB

had been found. The result was a pair of papers in the Astrophysical Journal (vol. 142 of 1965): one by Penzias and

Wilson detailing the observations, and one by Dicke, Peebles, Roll, and Wilkinson giving

the cosmological interpretation. Penzias and Wilson shared the 1978 Nobel prize in physics

for their discovery.

Today, the CMB radiation is very cold, only 2.725° above

absolute zero, thus this radiation shines primarily

in the microwave portion of the electromagnetic

spectrum, and is invisible to the naked eye. However, it fills the universe and can be

detected everywhere we look. In fact, if we could see microwaves, the entire sky would

glow with a brightness that was astonishingly uniform in every direction. The picture at

left shows a false color depiction of the temperature (brightness) of the CMB over the

full sky (projected onto an oval, similar to a map of the Earth). The temperature is

uniform to better than one part in a thousand! This uniformity is one compelling reason to

interpret the radiation as remnant heat from the Big Bang; it would be very difficult to

imagine a local source of radiation that was this uniform. In fact, many scientists have

tried to devise alternative explanations for the source of this radiation, but none have

succeeded.

Today, the CMB radiation is very cold, only 2.725° above

absolute zero, thus this radiation shines primarily

in the microwave portion of the electromagnetic

spectrum, and is invisible to the naked eye. However, it fills the universe and can be

detected everywhere we look. In fact, if we could see microwaves, the entire sky would

glow with a brightness that was astonishingly uniform in every direction. The picture at

left shows a false color depiction of the temperature (brightness) of the CMB over the

full sky (projected onto an oval, similar to a map of the Earth). The temperature is

uniform to better than one part in a thousand! This uniformity is one compelling reason to

interpret the radiation as remnant heat from the Big Bang; it would be very difficult to

imagine a local source of radiation that was this uniform. In fact, many scientists have

tried to devise alternative explanations for the source of this radiation, but none have

succeeded.

Why study the Cosmic Microwave Background?

Since light travels at a finite speed, astronomers observing distant objects are looking into the past. Most of the stars that are visible to the naked eye in the night sky are 10 to 100 light years away. Thus, we see them as they were 10 to 100 years ago. We observe Andromeda, the nearest big galaxy, as it was about 2.5 million years ago. Astronomers observing distant galaxies with the Hubble Space Telescope can see them as they were only a few billion years after the Big Bang.

The CMB radiation was emitted 13.7 billion years ago, only a few hundred thousand years after the Big Bang, long before stars or galaxies ever existed. Thus, by studying the detailed physical properties of the radiation, we can learn about conditions in the universe on very large scales at very early times, since the radiation we see today has traveled over such a large distance.

The Origin of the Cosmic Microwave Background

One of the profound observations of the 20th century is that the universe is expanding. This expansion implies the universe was smaller, denser and hotter in the distant past. When the visible universe was half its present size, the density of matter was eight times higher and the cosmic microwave background was twice as hot. When the visible universe was one hundredth of its present size, the cosmic microwave background was a hundred times hotter (273 degrees above absolute zero or 32 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature at which water freezes to form ice on the Earth's surface). In addition to this cosmic microwave background radiation, the early universe was filled with hot hydrogen gas with a density of about 1000 atoms per cubic centimeter. When the visible universe was only one hundred millionth its present size, its temperature was 273 million degrees above absolute zero and the density of matter was comparable to the density of air at the Earth's surface. At these high temperatures, the hydrogen was completely ionized into free protons and electrons.

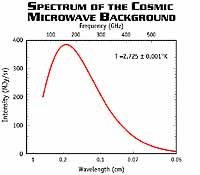

Since the universe was so very hot through most of its early history, there were no atoms in the early universe, only free electrons and nuclei. (Nuclei are made of neutrons and protons). The cosmic microwave background photons easily scatter off of electrons. Thus, photons wandered through the early universe, just as optical light wanders through a dense fog. This process of multiple scattering produces what is called a “thermal” or “blackbody” spectrum of photons. According to the Big Bang theory, the frequency spectrum of the CMB should have this blackbody form. This was indeed measured with tremendous accuracy by the FIRAS experiment on NASA's COBE satellite.

This figure shows the prediction of the Big Bang theory for the energy spectrum of the

cosmic microwave background radiation compared to the observed energy spectrum. Specifically a measurement was made of the surface brightness per unit frequency interval (𝛪𝜈), not 𝛪𝜆 - which is a per unit wavelength interval. The FIRAS experiment measured the spectrum at 34 equally spaced points along the blackbody curve.

The error bars on the data points are so small that they can not be seen under the

predicted curve in the figure! There is no alternative theory yet proposed that predicts

this energy spectrum. The accurate measurement of its shape was another important test of

the Big Bang theory.

This figure shows the prediction of the Big Bang theory for the energy spectrum of the

cosmic microwave background radiation compared to the observed energy spectrum. Specifically a measurement was made of the surface brightness per unit frequency interval (𝛪𝜈), not 𝛪𝜆 - which is a per unit wavelength interval. The FIRAS experiment measured the spectrum at 34 equally spaced points along the blackbody curve.

The error bars on the data points are so small that they can not be seen under the

predicted curve in the figure! There is no alternative theory yet proposed that predicts

this energy spectrum. The accurate measurement of its shape was another important test of

the Big Bang theory.

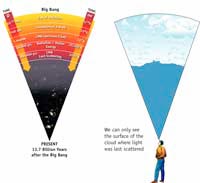

“Surface of Last Scattering”

Eventually, the universe cooled sufficiently that protons and electrons could combine to form neutral hydrogen. This occured roughly 400,000 years after the Big Bang when the universe was about one eleven hundredth its present size. Cosmic microwave background photons interact very weakly with neutral hydrogen, allowing them to travel in a straight lines.

The behavior of CMB photons moving through the early universe is analogous to the

propagation of optical light through the Earth's atmosphere. Water droplets in a cloud are

very effective at scattering light, while optical light moves freely through clear air.

Thus, on a cloudy day, we can look through the air out towards the clouds, but can not see

through the opaque clouds. Cosmologists studying the cosmic microwave background radiation

can look through much of the universe back to when it was opaque: a view back to 380,000

years after the Big Bang. This “wall of light“ is called the surface of last

scattering since it was the last time most of the CMB photons directly scattered off of

matter. When we make maps of the temperature of the CMB, we are mapping this surface of

last scattering.

The behavior of CMB photons moving through the early universe is analogous to the

propagation of optical light through the Earth's atmosphere. Water droplets in a cloud are

very effective at scattering light, while optical light moves freely through clear air.

Thus, on a cloudy day, we can look through the air out towards the clouds, but can not see

through the opaque clouds. Cosmologists studying the cosmic microwave background radiation

can look through much of the universe back to when it was opaque: a view back to 380,000

years after the Big Bang. This “wall of light“ is called the surface of last

scattering since it was the last time most of the CMB photons directly scattered off of

matter. When we make maps of the temperature of the CMB, we are mapping this surface of

last scattering.

As shown above, one of the most striking features about the cosmic microwave background is its uniformity. Only with very sensitive instruments, such as COBE and WMAP, can cosmologists detect fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background temperature. By studying these fluctuations, cosmologists can learn about the origin of galaxies and large scale structures of galaxies and they can measure the basic parameters of the Big Bang theory.